Part Two

Now, I ask you to allow me to lead you for a moment into the realm of abstract concepts, which, for people like you, accustomed to noble pursuits and serious scientific inquiry, is not an alien world but, on the contrary, a well-known domain.

When we delve into the depths of our own being and closely examine our mind, we discover within it two impulses, two equally natural, innate, indispensable, and indestructible needs concerning the pursuit of truth: the need for faith and the need for reasoning.

The need for faith is so strong, so powerful in man, that he is sometimes inclined to believe too much, to believe in everything, rather than to believe in nothing; he is ready to renounce reasoning rather than completely abandon faith. This disposition is the primary cause of superstitions and credulity.

Yet no less strong, no less powerful in man is the need for reasoning. Subject to this need, he is sometimes ready to believe in nothing rather than blindly believe in everything; he is more willing to renounce all faith than to deny reason. This is precisely one of the causes of unbelief.

All religions that are the work of human hands can be classified under one of these two categories: sensual religions (idolatry, paganism, Mohammedanism) and religions of pride (heresies and rationalism). The fundamental principle of all sensual religions is: “Everything to authority, nothing to reason.” Conversely, the main principle of all religions of pride is: “Everything to reason, nothing to authority.” Only the Catholic religion, my brothers, which has its origin in God and is His work, says to man: “Respect authority and use reason wisely.” For, as we already know, Saint Paul said that we should first strive to submit our reason to the obedience of faith and be convinced that this homage is a rational act: *Redigentes intellectum in captivitatem fidei. Rationale obsequium vestrum* (2 Corinthians 10:5; Romans 12:1).

Thus, while sensual religions lead man to the abuse of faith, and religions of pride draw him into the abuse of reason, only Catholic teaching places man on a rational middle ground, equally distant from both abuses, from both opposing extremes.

The teachings of false religions, whether sensual or prideful, are erroneous and false precisely because they lead man to extremes, to abuse, to exaggeration. For any scientific system pushed to excess is logically flawed, just as any human act carried to excess is morally deficient. Conversely, Catholic teaching is true precisely because it places man in the middle of these two extremes. For both truth and virtue always occupy a middle position: *Medium tenuere beati!* And just as truth is the virtue of the mind, so virtue is the truth of the heart.

Sensual religions say to man: “Believe without reasoning,” while religions of pride declare: “Reason without believing.” For to merely suppose, which is the extent of the rationalists’ faith, is not to believe at all. Thus, while all sensual religions end in debasing man, plunging him deeper into errors, admitting no form of knowledge, and culminating in ignorance; and while all religions of pride likewise end in destroying man, casting him into the abyss of doubt, stripping him of all faith, and concluding with unbelief—Catholic teaching, which recommends faith while guiding reason, which commands belief while fostering the development of talents and abilities, and knows how to restrain man at the point where faith remains rational and reason remains believing, thereby saves man and elevates him, as it were, above himself. In its final outcome, it grants faith and knowledge, which are the essential, primary conditions for all civilization and progress.

Finally, while sensual religions, though satisfying man’s need to believe, neglect and fail his need to reason, and religions of pride, having satisfied the need to reason, bypass and deceive the need to believe—both, in this way, cast man outside the natural order of things. For the natural order for man is one in which he can unite both reason and faith. In contrast, Catholic teaching, by kindling faith without obstructing the proper and lawful development of talents and abilities, places man in a natural state, a perfect state, uniting authority with knowledge, reason with faith, and thereby solving the great task concerning the human mind.

It was precisely this teaching that Catholic reason embraced from the earliest times of Christianity, seeking to create a truly Christian philosophy, a philosophy truly natural in its principle.

**6.** Behold, my brothers, the great event, a new, extraordinary, magnificent, and wondrous event that occurred in those ages. While outside the Church, knowledge destroyed faith, or faith placed barriers to the development of knowledge, within the bosom of the Church, knowledge defended faith, and faith fostered knowledge. While outside the Church it was almost impossible to find wise men who possessed faith or believers who had knowledge, within the Church one saw wise men, Christian philosophers, joining together without any prior agreement, converging on a shared idea, meeting in a common, noble, and lofty sentiment, and forming a marvelous and astonishing array of elevated minds. These minds advanced faith to the simplicity of children on one hand, while on the other, they developed reason to the heights of genius. There were Tertullians, Origens (so long as they adhered to the Church’s teaching), Lactantiuses, Arnobiuses, Irenaeuses, Athanasiuses, Gregory Nazianzens, Cyrils, Basils, Chrysostoms, Hilarys, Ambroses, Jeromes, Augustines, Leos, Peter Chrysologuses, and Gregory the Greats. What men these were, my brothers! In them were contained all talents combined with all virtues. What deeds they accomplished, what battles they waged to defend and develop true Christian teaching!

I will cite only one work, Saint Augustine’s *City of God*, a staggering work due to the depth of its insights, the breadth and loftiness of its teaching, where one can find the refutation of all errors, the exposition of all truths, and the explanation of mysteries in the theological, philosophical, and even natural domains. This single work surpasses all the works of ancient philosophers, who, I boldly confess, in my eyes appear as children compared to a mature man, as students before a master, in the presence of the immortal creator of this masterpiece of human reason.

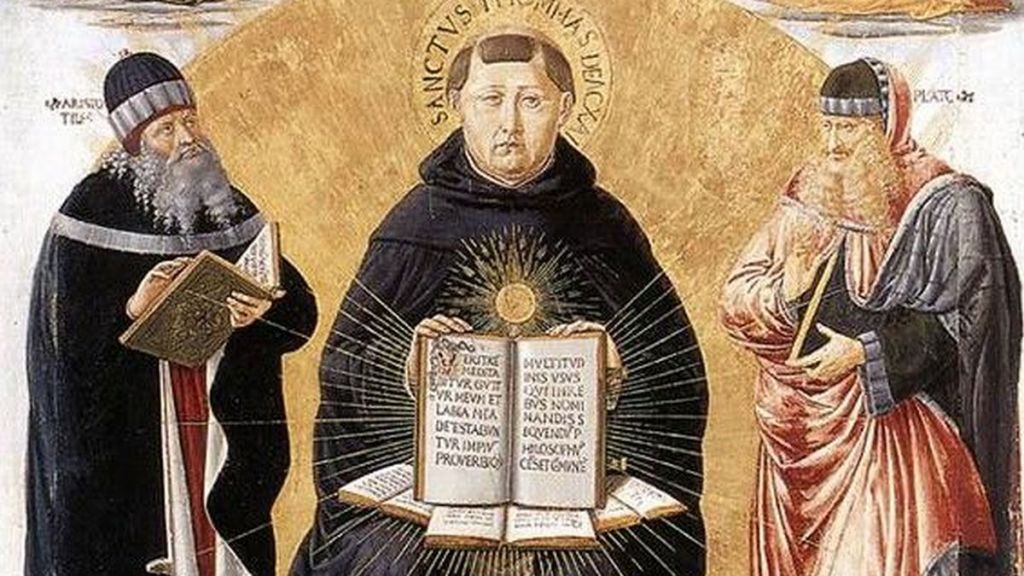

During the influx of northern peoples into the rest of Europe, Catholic reason seemed to slumber in silence and inactivity. All learning became nearly impossible at that time. Frightened sciences and literature had to seek refuge in monasteries to escape the fury of the barbarians. But as soon as divine Providence accomplished the great work of creating and shaping Christian society on the ruins of the old pagan society, Catholic reason awoke with new power and fullness of life. In the persons of Bernards, Anselms, Albert the Greats, and Saint Thomases, it reached the highest peaks of greatness.

Saint Thomas, my brothers, what a man, what a genius! He is human reason elevated to its highest potency. Nothing can surpass the strength of his reasoning except the vision of things in heaven itself. Here on earth, reason can neither rise higher nor see more clearly. One could repeat of Saint Thomas what Saint Augustine said of Saint Jerome: that no one ever knew what Thomas did not know—*Nemo scivit, quod Thomas ignoravit*. This unique man, whose life did not span half a century, saw everything, knew everything, and explained everything. There is not a single error he did not foresee, conquer, and utterly destroy. His *Summa* is the most astonishing, profound, and marvelous book ever produced by a human hand, for the Holy Scriptures came from the hand of God. Saint Thomas explained not only the theological world and the philosophical world but also the physical world. His genius, illuminating his own age and those that followed, shed light upon them, brought scientific order, ensured true progress, and cast upon the sciences and religion a brilliance that will never fade.

This splendid period of Christian learning, my brothers, is not sufficiently known, or at least not sufficiently contemplated or deeply studied. For if it were properly examined, then you, especially the French, and even more so you Parisians, would feel a holy pride, a holy glory. Never before or since has France, has Paris, been greater or more renowned in terms of enlightenment. Never has it more abundantly or widely disseminated the treasure of profound truths and useful knowledge than in that era when Albert the Great, Saint Thomas, and Saint Bonaventure taught at your Sorbonne to countless thousands of students who flocked to it from all corners of the earth. From there, these great men shone with the brilliance of their learning, sowing the seeds of true civilization and true wisdom everywhere.

This is the period when human reason was most thorough because it had the greatest faith. It was then that the foundations of Christian learning, Christian literature, Christian art, and Christian civilization were laid—foundations of which Europe now boasts and which it has sometimes misused against itself. In that era, the physical sciences reached astonishing development, no less than theological, philosophical, political, and moral sciences. Yet this age, through the malice and injustice of recent times, has been called an age of barbarism. In this age, the Christian genius, inspired by faith, made three great inventions that changed the face of the world: gunpowder to rule the earth, the compass to rule the sea, and the printing press to rule the mind and develop it.

Such were the benefits that Catholic reason received for its steadfast fidelity to the word of God. Its highly religious philosophy was also profoundly lofty and useful, for it was rooted in the natural principle of the perfect human being, which is the development of reason under the wings of faith.

I will add that Catholic, philosophical, Christian reason, by the very fact that it was inspired by the word of God, had to be enduring in its foundation. Please pay close attention to me.

**7.** Everything in the world is either matter, spirit, or a combination of spirit and matter. Pure spirits are God and the angels; pure matter consists of all natural, tangible, and corporeal creations; the combination of matter and spirit is man. Since things that are mutually opposed and situated at extremes can only be properly understood in a being composed of both, and since man combines spirit and matter, it follows that spirit and matter can only be best understood in man. Therefore, the first question that true philosophy must ask is: *What is man?*

There are two types of composition: artificial, accidental composition, which gives rise to something complex that can only be considered a unity in a moral or improper sense, such as a building, a heap of grain, or an army; and natural, essential composition, which gives rise to something complex that is truly and strictly a unity, such as a tree, an animal, or a man. To the question, *What is man?* the entire human race responds: Man is a creature composed not artificially or accidentally but naturally and essentially of spirit and matter, of soul and body, in such a way that these two substances form a unity in man, an individual, a single person.

Do you want proof that humanity has always understood man in this way? Listen to the language of all people, all nations, and all times. Never and nowhere has it been said: Peter’s spirit thinks, his mouth speaks, his legs walk, his hands act; rather, it is said: Peter thinks, Peter speaks, Peter walks, Peter acts. This means that the entire human race, in its natural logic, has not regarded human actions as mere bodily movements without spirit or as purely spiritual activities without the body, but as actions of a soul essentially and inseparably united with the body, or of a body animated by the soul, as actions of a man constituting a real and indivisible unity. This is what Christian philosophy expressed in these simple yet profound words: *Actiones sunt suppositorum. Actiones sunt conjuncti* (Actions belong to the subject. Actions are of the composite).

But philosophical reason, which sought to rely solely on its own powers, disregarding the voice of humanity, the universal judgment, which is the voice of nature and truth, answered this great question—*What is man?*—in an entirely different way. It replied: Man is a being composed of soul and body, constituting a unity only in a moral, improper, and accidental sense. For Plato, man is a spirit with a body as an appendage. As Cicero said of the Platonists: *Ajebant appendicem animi esse corpus* (They said the body is an appendage of the soul). A Catholic sage of our time echoed this with greater elegance, though no greater truth, saying: Man is a mind served by tools. One definition is as valid as the other, for both are fundamentally false. For Plato, and later for Descartes, the soul is united with the body in man as an agent to an object moved, as a rower to a boat—a union that, as you see, my brothers, is as temporary, accidental, and changeable as can be imagined. For the principal and the appendage, the master and the servant, the agent and the moved, the boat and the rower, are not one but two. Applied to man, this is entirely false, for in him, spirit and body are united in an essential, inseparable manner.

**8.** Now consider, my brothers, the consequences of this erroneous teaching about the nature of man.

As soon as rational philosophy, or philosophical reason, failed to acknowledge the principle that the human soul and body are two things that mutually complement each other through their union, sharing one and the same being and forming a composite yet inseparable unity, and began to view man as an accidentally composed being, with the soul and body as two parts, each complete and whole in itself, each with its own separate being and activities, this philosophical reason was forced to invent laws and systems of connection to explain their marvelous harmony, whereby sensory impressions pass to the soul and the commands of the will manifest in the body. From this arose three famous systems, revived by modern thinkers under the names: *Harmony or Pre-established Harmony*, *Occasional Causes*, and *Physical Influence*.

However, since these supposed laws and systems explained nothing and could explain nothing, some declared: “If the human soul acts entirely on its own, forming ideas without the participation of the body, what need is there for the body, and what is this body? We do not understand any of this.” To resolve the issue briefly, they denied the reality of the human body, and having denied the reality of the human body, they were compelled to deny the reality of all bodies in the universe. Thus arose *idealism*.

Others, more logical (these were the Epicureans), said: “If the body, independently of the soul, has its own being; if the body exists as something moved in relation to a mover, like a boat to a rower, like a servant to a master; if this body, receiving all impressions from external objects, feels on its own, performs its own movements and activities; what need is there for a soul? Moreover, we see the body, we touch the body, but we do not see the soul. Therefore, if anything is certain, it is surely that there is no soul at all, or that what we call the soul or spirit is merely a vain word, or that what we call the soul is nothing but the perfection of bodily organization.” Thus, they denied the existence of the spirit in man, and proceeding from one consequence to another, having denied the spirit in man, they had to deny the existence of any spirit in nature; they therefore denied the existence of God. Thus arose *materialism* and *atheism*.

Hence, all ancient and modern philosophy has always been divided between these two systems, for by relying solely on itself, it rejected the fundamental principle of the true knowledge of man, namely, the principle of the inseparable unity of the human soul and body.

The philosophy established by Catholic reason never knew this destructive division. It was never idealistic nor materialistic, much less atheistic, for it regarded the soul and body in man as constituting a single natural whole, an essential, indivisible whole. The starting point of its psychology was this principle: *Anima intellectiva est forma substantialis corporis humani* (The intellectual soul is the substantial form of the human body)—a profound and crucial principle, the principle of true philosophy. Due to its importance, the Council of Vienne in 1311 sanctified it with these words: *Qui pertinaciter asserere praesumpserit animam intellectivam non esse formam per se essentialiter corporis, haeriticus censendus est* (Whoever obstinately presumes to assert that the intellectual soul is not essentially and of itself the form of the body is to be considered a heretic).

**9.** Let us not reproach the ancient philosophers, my brothers, for not knowing this great and crucial truth. Recall, according to the teaching of Saint Paul, that Jesus Christ did not become man for man’s sake; rather, man was created with a view to Jesus Christ. Just as an artist, when crafting a statue of a distinguished person, takes great care to create a precise, smaller model or likeness, so too, says Saint Paul, God, in creating man, made only a type, a model, an image of Jesus Christ, who was to come into the world in time: *Adam primus, qui est forma futuri* (Romans 5:14, The first Adam, who is a figure of the one to come).

Since man is the image and likeness of Jesus Christ, he can only be known where Jesus Christ is known. For one cannot know a likeness without having some notion of the person it represents. The ancient philosophers, having no concept of Jesus Christ, could not, therefore, know man. The Jews knew man imperfectly, for they knew the Messiah, Jesus Christ, only vaguely through prophecies and tradition. Only among Christians, who know Jesus Christ perfectly, could man be perfectly known. The Christian dogma that in Jesus Christ, humanity and divinity are inseparably united without confusion of essence in the unity of one person served as a light for Christian philosophers, especially for Saint Athanasius, the true founder of Christian philosophy, to draw this conclusion: that in man, the soul and body are inseparably united with each other without confusion of essence in the unity of the same being. In this way, the human body is a perfect body but has no being except through and in the soul that sustains it, just as the humanity in Jesus Christ is perfect but has no personality except in and through the person of the Word that dwells in it. Thus, by virtue of the Catholic dogma that presents Jesus Christ as uniting two natures—the divine nature fused with the human nature—not in an accidental manner but inseparably, forming the most perfect and strictest unity, our sages, in the light emanating from the face of Christ and reflected in man, recognized and declared that “the rational soul and body form an inseparable unity in man, just as divinity and humanity are inseparably united in Jesus Christ”: *Sicut anima rationalis et caro unus est homo; ita Deus et homo unus est Christus* (As the rational soul and body are one man, so God and man are one Christ), as stated in the creed attributed to Saint Athanasius.

Thus, my brothers, these great men drew the necessary light from the altar to illuminate their school; they borrowed light from religion to enlighten their learning; with the light taken from the word of God, they explained the nature of man, and in this way alone did they achieve the happiness of knowing that nature: *Beati qui audiunt verbum Dei, et custodiunt illud* (Blessed are those who hear the word of God and keep it, Luke 11:28).

**10.** Now consider the importance and thoroughness of these principles of Christian teaching.

In the theological order, all heresies can be grouped into two categories: the heresy of the fantastics, who deny the reality of the body or humanity of Jesus Christ, and the heresy of the humanitarians, who deny His divinity. Similarly, in the philosophical order, all errors reduce to the following: the errors of materialists, who deny the existence of the spirit in man, and the errors of idealists, who do not acknowledge his bodily component. But, I repeat once more, just as all heresies in the theological order have been overcome and annihilated by the Catholic teaching of the inseparable unity of divinity and humanity in Jesus Christ, so all philosophical errors are refuted by the teaching of Christian philosophy: that man is an inseparable unity of soul and body, and that every true theology, like every true philosophy, comes down to these words of Saint Athanasius cited above: *Sicut anima rationalis et caro unus est homo; ita Deus et homo unus est Christus*.

It is objected against the Catholic reason of the Middle Ages that the philosophy derived from it was overly concerned with trivial matters, while modern philosophy, as they say, deals with the most important questions. But even if we accept this as true, upon careful reflection, we must find here praise for ancient philosophy and censure for the modern. Christian philosophers had a universal symbol of truth, and with the light drawn from religion, from the voice of nature, and from common, universal notions constituting the heritage of humanity, they resolved the most important questions in the philosophical order. It is therefore entirely natural that at times, this intellectual activity could turn to subjects whose importance and value not everyone can appreciate. This is a natural consequence of the progress of human reason: having grasped and secured what is necessary and useful, it later begins to think about what is convenient, refined, pleasant, graceful, and even what borders on frivolity. It is like a wealthy man who, having secured his livelihood, willingly spends his surplus income on luxurious and recreational items.

But as for modern philosophy, by its reckless separation from religion, having lost knowledge of all truth, it has descended to debating whether there is truly even a single truth and whether man possesses the means to know it. It is therefore natural that it could not be inclined to discuss secondary questions; it is natural that it had to limit itself to inquiries that would clarify the existence of God, the spirituality of the soul, and the origin of the world, for it has fallen into the deepest shadows, into the most complete ignorance regarding these primary truths that constitute the essential nourishment, the intellectual bread, and the foundation for all science and all religion. Can it seem strange, then, that a pauper lacking daily bread does not think of amusements, does not seek entertainment or spectacles? Can one dream of luxuries when lacking even rags to cover the body’s nakedness? The supposed importance of the questions discussed by modern philosophy is nothing but clear evidence of its poverty, its misery, its wretchedness. Instead of boasting and inflating itself, it should acknowledge its defeat and humiliation. Its claims to some right to greatness and primacy over Christian philosophy are as laughable and unreasonable as the claims of some Hottentot or wild Oceanian to superiority over a European, over a cultivated man, merely because his tastes are simple and his manners crude.

Moreover, Catholic reason, by the very fact that it is inspired by the word of God, faith, and the teaching of the Church, is also certain in its method, natural in its order, and grounded in its principle.

**11.** In all great questions in the scientific order, sages always divide into opposing, contradictory opinions that fight against one another.

Such two opinions can never both be equally true, for no truth can ever reside simultaneously in two contradictory judgments. Nor can both be equally false, for they are in conflict, and thus both must have some strength. It is impossible to fight without strength. And if they have strength, they must necessarily contain some truth or at least stand in some relation or kinship with it, for the entire authority of our judgments depends solely on the extent to which they are true, on how much truth they contain. Outside the Church, there is nowhere any truth without some admixture of error; but it can also be said, conversely, that there is no error without some kinship, however distant or hidden, with truth.

By taking sides in this struggle, we contribute to its intensity. The only way to end it is to take a middle position, to reconcile the conflicting opinions by uniting into one whole everything true that is found in both opposing systems. Such was the method of Christian philosophy. Having learned from Saint Paul not to reject any system *a priori* without thorough analysis, even if it seems erroneous, but to probe the spirit of each, to select and appropriate everything just, reasonable, and true in it—*Omnia autem probate, quod rectum est tenete* (1 Thessalonians 5:21, Test all things; hold fast to what is good)—Christian philosophy, in questions of every kind, always took a middle position between two extreme opinions. It selected everything true it could find in both, combined these truths, and in this way resolved the most difficult questions for human reason.

Thus, the method of Christian philosophy, of Catholic reason inspired by Christianity, was true eclecticism—not the eclecticism offered by modern times as the only way to attain truth, as the only philosophy capable of standing on the ruins of eighteenth-century systems.

For consider this carefully: just as one cannot choose the good without first knowing what is good, so too one cannot choose the true without first knowing what is true. Now, the philosophical reason of modern times, accepting no truth that is not its own acquisition and starting from doubt or nihilism, does not possess and cannot possess any such truth to guide its choice, yet it is precisely from such a choice that all truth is supposed to arise. Therefore, modern eclecticism, rejecting all traditional, universal, and religious truth, is a kind of mad endeavor, akin to trying to read in darkness without light, to cross a desert without a guide, to fly like a bird without wings, to build without foundations, to speak while mute, or to reason without reason. It is a degenerate eclecticism, an absurd eclecticism, a deceitful eclecticism, which, stripped of its mask, is nothing but simple indifference to every error, arising from the impossibility of knowing truth and the loss of hope in discovering it. It can be summed up in these words: “Believe as you please, and live according to what you believe.”

Such was not the eclecticism of Christian philosophy. In the word of God, which it obediently heeded and faithfully guarded, it found a ready touchstone, the necessary light by which it could discern the truth of all systems and opinions. It thus had a certain guide for making its choices. It could select everything true and good found in the writings of all ancient philosophers; it was certain in its method, which ultimately ensured the advantage of being rich and fruitful in its consequences, as we shall see in the forthcoming third part.

**Support Us**

**On Catholic Reason in the Early Centuries of Christianity (Part 1)**

*Religious-Moral Journal: A Periodical for the Edification and Benefit of Both Clergy and Laypersons. Vol. 24, No. 4 (April 1853)*

**(1)** In Paris, the place called Maubert is properly the *Place of Magnus Albertus* (Albert the Great), where Albert taught, for no hall or courtyard could contain his numerous listeners.

**(2)** What I call philosophy, said Clement of Alexandria, is neither the wisdom of the Stoics, nor of Plato, nor of Epicurus, nor of Aristotle; but it is a selection made from all these teachings, of everything they may contain that is true, friendly to good morals, and consistent with religion (*Stromata*, Book 1). According to Saint Jerome, it was necessary to study pagan writers, to appropriate and turn to the glory of religion everything good and true that could be found in them, much like the Hebrews who took the silver vessels of the Egyptians and used them for the glory and service of the Ark. Thus, Christian philosophers, with their eyes turned to religion, selected from philosophical teachings what could serve to defend and develop religion. Such a form of eclecticism is easily understood. But the eclecticism in which everything depends on arbitrary choice, which must even choose the rule guiding its choice, which seeks to select everything true without knowing what truth is, and which does not even know whether truth exists or whether man has the means to discover it, is utterly incomprehensible. Such eclecticism is and can only be the result of blind chance or delusion, a chaotic mixture of remnants from various systems, dreams, and aberrations of human reason; it is and can only be confusion and disorder.

—

Religious and Moral Diary: a journal for the edification and benefit of both clergy and laity*, Vol. 24, No. 4 (April 1853).

Leave a comment