*Blessed are those who hear the word of God and keep it.*

Luke 11:28

1. The Gospel of Jesus Christ cannot be better explained than by the Gospel itself.

Do you wish to know why, in today’s Gospel, Jesus Christ calls blessed those who hear the word of God and keep it? It is because, as He Himself said in another Gospel: “Man does not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God” (Matthew 4:4). This means that just as food sustains natural, material life, so the Word of God, which is truth, sustains spiritual life.

From this, my brethren, it clearly follows that any scientific system that substitutes mere reasoning for faith, or human words for the Word of God, is by that very fact destructive and criminal. Such a system kills the noblest part of a person by robbing them of their intellectual life.

This is precisely what we have seen the philosophical mind do, and as we shall see later, it will always do, when it seeks to act solely on its own upon human minds. So much so that wherever you find, in the intellectual world, minds deadened by doubt or spiritual corpses, you can be certain that the philosophical mind has passed through, bearing poisoned nourishment in its hand. These dreadful murders of souls, far more horrific than the slaughter of bodies, are its doing.

In contrast, any scientific system that draws its inspiration from the Word of God, that is grounded in the Word of God—that concise, all-powerful Word, which in another place in Holy Scripture is called the true bread of life and understanding, and the water of salvific wisdom: *Panis vitae et intellectus, et aqua sapientiae salutaris* (Ecclesiasticus 15:3)—such a system is life-giving and salvific. It brings the reward, happiness, and blessing that Jesus Christ today promised to those who hear the Word of God and keep it.

This is how the Catholic understanding operated from the beginnings of Christianity until the sixteenth century. For this reason, it was able to create a true philosophy, a philosophy that is a friend and ally of religion. This philosophy was rational in its aim, natural in its principles, solid in its foundation, certain in its method, blessed in its outcomes, and beneficial in its consequences. This is what we intend to demonstrate today.

Having considered the misery, harmfulness, and shame of the philosophical mind in pagan centuries, it is fitting to reflect on the power, benefits, and glory of the Catholic understanding in Christian centuries. This contrast will further convince us that, in both the scientific and religious order, there is no blessedness or happiness except in listening to the Word of God with submission and faithfully keeping it: *Beati, qui audiunt verbum Dei et custodiunt illud.*

Let us begin by imploring heavenly assistance through the intercession of Mary: *Hail Mary.*

Part One

2. One of the philosophers of the seventeenth century (Locke), who was nothing more or less than a philosopher, and whom the eighteenth century’s anti-Christian fanaticism made one of the renewers and idols of modern philosophy, nevertheless made a profoundly important observation. He said that it is one thing to seek to discover some hidden truth through reasoning, and quite another to seek to understand and gain conviction about a truth already known.

In these few words, my brethren, lies the entire history of philosophy from the beginning of the world to our own days. For philosophy has been nothing other than either the science of discovering hidden truths or the science of proving, developing, and applying known truths to the perfection of humanity and the happiness of society. Thus, philosophy—forgive my expression—has been either *searching* or *proving* (1).

(1) It is a remarkable and strange thing that philosophers, who have seen or thought they saw so many things, did not distinguish these two different kinds of philosophy, which are connected to the religion of the Indians, which originate in the religion of peoples, and whose differences are evident to any thorough observer of the philosophical movement by which the human mind has progressed. It is remarkable and strange that minds that made such great use of reasoning did not consider that, even if philosophy were nothing but the science of truth, there are necessarily two distinct kinds of philosophy because there are two ways of approaching this science: one, which is the science of discovering all truths through human faculties alone; and another, which is the science of better and more precisely knowing, clarifying, and confirming, through proofs gathered from all sides, those truths already proclaimed by religion or universal tradition. For in the pursuit of truth, one can proceed from the known to the unknown or start from the unknown toward the known; one can proceed either according to the principle that reason must find for itself what it is to accept as truth, or according to another principle: that reason should limit itself to understanding, proving to itself and others truths already known from elsewhere.

Let us set this aside, however. People did not wish to see that, under the same name of the science of wisdom, there have always been two entirely different kinds of philosophy in the world, each with its own characteristics, principles, systems, and consequences. They did not wish to recognize as true philosophy the *proving* philosophy, which alone has been and always will be the true philosophy. It was overlooked, unnoticed, even though it stood right beside us, full of life and shining with the light of truth. And if it was noticed at all, it was ignored, met with a glance of proud disdain or condescending pity. The *searching* philosophy, the philosophy of reason divorced from religion, confident in itself and aiming to conquer truth by its own strength, was recognized as the only philosophy. Since such a philosophy existed only among the most renowned pagan peoples of antiquity—in Athens and ancient Rome—true philosophy was sought only there. From this pagan, sensual, and ignoble civilization, which vanished from the world leaving nothing behind but traces of blood and mud alongside beautiful books and noble statues, people demanded sciences and systems that were to constitute the happiness and glory of Christian peoples and nations and form the foundation of their enlightenment. This is the philosophy they sought to revive in recent times. This proud and foolish idea gave rise, in the last three centuries, to so many supposed renewers of philosophy, who boldly declared to the whole world that true philosophy was unknown before them, who proclaimed their systems and teachings as entirely new discoveries, and who, with the greatest solemnity and heroic courage, heedless of the immense ridicule they brought upon themselves, presented themselves as earthly oracles and torches of humanity.

—

The *searching* philosophy rejected any truth that was not its own conquest; the *proving* philosophy eagerly embraced every truth it encountered. The *searching* philosophy is the natural enemy of the religious principle; it does not believe in it and hates it as a rival. Even when, as in our days, it sometimes turns a friendly face toward religion, pretending to ally or befriend it, it does so only to humiliate, subdue, conquer, and destroy its sister. Just as a highway robber might join a solitary traveler and accompany him until he can safely attack, rob, and kill him. In contrast, the *proving* philosophy, delighted to be enlightened by the light that comes from above through religion, is a friend and sincere ally of the religious principle. It works only to develop it, to strengthen it in the minds of people, and to defend it against the assaults of error and passion.

Thus, at its core, the *searching* philosophy is human reason that accepts no bridle, recognizes no law, submits to no authority, and even sets aside God Himself when it comes to His truths and beliefs. It is the absolute independence of reason; it is a freedom of thought pushed to the point of license, almost to madness (2).

(2) Saint Paul condemned this proud arrogance of the philosophical mind, which believes it can suffice for itself, with these profoundly significant words: “If anyone thinks he knows something on his own, not only does he know nothing, but he does not even know the way to know anything” (1 Corinthians 8:2). Saint Augustine observed that it is in the nature of a rational creature, when seeking to learn something, to begin with belief, and that, in both the scientific and religious order, authority must always precede reasoning.

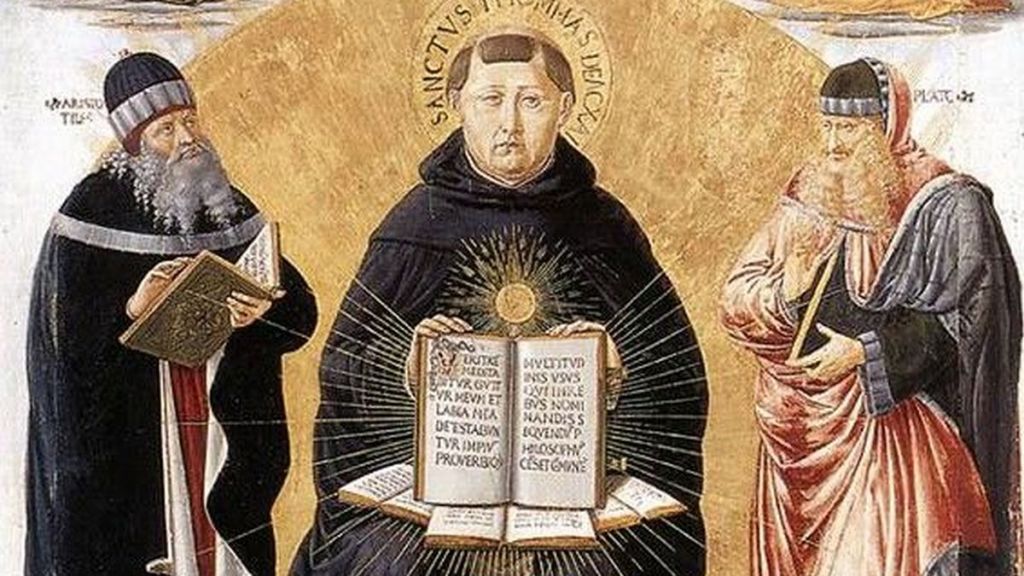

In contrast, the *proving* philosophy, at its core, is nothing other than human reason that accepts a bridle, recognizes law, respects religious authority, and what Saint Thomas calls the common conceptions of the human spirit: *conceptiones animi communes*. It is a reason that willingly submits to God, depends on God, and confines the use of its freedom within the boundaries set by God, knowing well, as Holy Scripture says, that God is the creator and Lord of all knowledge and that every human thought should rise to God and aim toward Him.

Thus, the *searching* philosophy takes doubt as its starting point; the *proving* philosophy takes faith. The *searching* philosophy relies on human words and prides itself in them; the *proving* philosophy relies on the divine Word and glories in it. It listens to it, faithfully keeps it, and by this very act attains happiness, for it can create a scientific system with a noble and righteous aim in its pursuits: *Beati qui audiunt verbum Dei, et custodiunt illud.* Such was the philosophy, my brethren, that the Catholic understanding produced in the earliest times of Christianity.

—

3. Jesus Christ says in the Gospel that the Kingdom of God is like a treasure hidden in a field, which, upon discovering its value, a man eagerly buys, selling all that he has so that, becoming the owner of that field, he may enrich himself with the treasure it contains. “Now, this heavenly kingdom of which Jesus Christ speaks here is the present Church,” as Saint Gregory said: *Regnum Coelorum praesentis temporis Ecclesia dicitur* (Homily 12 on the Gospel).

In this very Church, my brethren, and nowhere else, lies hidden, veiled in the mysteries and in the most sacred depths of faith, the treasure of the one and complete truth. The ancient sages, the true philosophers of the first centuries of Christianity, upon learning that this treasure was in the field of the Church, sold everything, sacrificed everything—their talents, their possessions, even their lives—and bought that field, becoming possessors of that treasure. For this reason, Saint Paul said to them: “Now you are enriched in everything, in every kind of truth, grace, and virtue” (*In omnibus divites facti estis*, 1 Corinthians 1:5). From then on, as is rightly inferred, they should have ceased, and indeed did cease, all rational searches for truth.

As for the ancient philosophers, they can at least be partly excused for being, as Saint Paul calls them, *searching* philosophers: *Graeci sapientiam quaerunt* (The Greeks seek wisdom). Paganism offered them nothing but absurdities that could not be accepted, cloaked in shameful, repulsive, and cruel rituals. The traditions of peoples had been so distorted, obscured, and corrupted that only faint traces of them could be discerned. Thus, it should not seem entirely strange that these people were compelled to seek truth through their own reason. But as for the first Christians, who through the Church and in the Church found the treasure of all truth; who already knew God and His attributes, the world and its creation, humanity and its origin and purpose, the law and its duties, sin and the true way of atoning for it, punishments and rewards in the afterlife and their eternity, and who knew all this in the clearest, purest, most thorough, certain, complete, and perfect manner—for these people, I say, what use would there be in searching for what was already before their eyes, what they held in their hands? For this reason, Tertullian said: “After receiving the Gospel, we no longer need to engage in philosophical inquiries; after Jesus Christ, we no longer need to devote ourselves to curious investigations.”

—

This does not mean, however, that the ancient Christian sages entirely despised secular knowledge, human knowledge, or purely philosophical knowledge. Rather, in the beautiful and simple words of one of the earliest Church Fathers, Clement of Alexandria, these sages first nourished themselves with faith as with bread, as the substantial and nourishing food of the soul; and only then did they turn to human knowledge, as one might partake of other dishes after a hearty soup, or enjoy a sweet pastry or fruit after a meal.

In this way, these great Christian figures understood the knowledge derived from the Word of God and the knowledge derived from human words. By this alone, they happily laid the foundations for a philosophy with a well-considered, rational aim.

—

4. However, from the fact that the Fathers and Doctors of the Church primarily insisted on the need for a *proving* philosophy, it would be unjust to accuse them of seeking to overly restrict or even overthrow the rightful claims of human reason; of wishing to prohibit the exploration of all truths, even natural ones; or of intending to limit reason solely to proving to itself and others, through natural means, only revealed truths.

According to their opinion and practice, true philosophy should indeed begin with the order of faith and then proceed to the order of concepts, rather than starting with the order of concepts to later ascend to the order of faith. For no method of proceeding is more fitting for human reason than this. Reason, in accordance with experience, demonstrates that by beginning with faith and preserving faith, one arrives at concepts and understanding; but conversely, by starting with concepts and understanding, one loses faith and never attains the ability to understand or form concepts: *Nisi credideritis, non intelligetis* (Unless you believe, you will not understand). In such a case, one arrives only at the complete concept of absolute doubt, that is, the concept of sorrow and despair, which, originating in injustice, produces only iniquity: *Ecce concepit dolorem, parturivit injustitiam et peperit iniquitatem* (Behold, he has conceived sorrow, brought forth injustice, and given birth to iniquity, Psalm 7:15).

But by maintaining that the primary task of true philosophy is to closely examine, weigh, confirm, develop, prove, and increasingly understand what is less comprehensible in truths drawn from the source of religion, from sound reason, from tradition, and from universal reason, it is by no means denied that philosophy has a secondary aim: the continuous further search, on the path to knowing things whose knowledge is possible, to explain the how and why of things already accepted as certain and true, nor is it denied the possibility of drawing conclusions that do not exceed the bounds of the order of faith.

Moreover, by asserting that reason must receive from faith, and not create through its own reasoning, the primary truths and universal principles that constitute reasoning itself, it is by no means forbidden for that same reason to search for lesser truths and secondary principles. It is not denied the ability to uncover as many unknown and new truths as can be derived through reasoning, nor to apply them to the development of the mind, to the improvement of the moral and physical state of both individuals and society.

Now, such deduced truths, which the consensus of the wise confirms, which society sanctifies by its acceptance and puts into circulation as useful products, as untainted currency—such truths, I say, are they not true discoveries, true conquests of reason, testifying to its power and glory?

Did not Saint Augustine and Saint Thomas, the two greatest geniuses of the world, starting from the order of faith, ascend to the highest peak in the order of concepts? And yet, their steadfastness in faith did not in the least hinder their astonishing intellectual progress, nor did their intellectual progress harm their perseverance in faith.

Did they not, through their believing reason, make countless and precious discoveries concerning the principles, proofs, causes, and consequences derived from the greatest truths of revelation, as well as their relation to truths in the natural order of things? Did they not expand the horizon for human reason, open new paths for genius to inventions and inquiries, enriching knowledge with treasures of growth and light that constitute the world’s admiration and would even bring it happiness if they had not been buried under the dust of indifference and forgetfulness?

Are these two examples not irrefutable proof that the Catholic understanding, by limiting itself to the bounds of proving and developing truths taken from universal reason, tradition, and religion, established a true and rational philosophy in its aim? For only by aiming at such a goal can one walk the path of knowledge without falling, progress without erring, and rise high without becoming dizzy.

For this reason, in the centuries under discussion, it was said to reason that it should take known truths as its starting point, believe in them, and rest upon them. In this way, reason was not deprived of its freedom but was restrained from license. It was forbidden only from turning against its own nature; it was prohibited from using itself unlawfully, immoderately, and destructively, while no barrier was placed on its ability to make natural, moderate, and righteous use of itself, which would preserve it, enhance it, and continually advance it.

Absolute independence is not the lot of humanity, either in the scientific order or in the social order. Just as in the social order, there is freedom only insofar as one submits to and fulfills the law, so too in the scientific order, there is no true knowledge except by believing in the primary truths, universally recognized truths preserved by true religion, and in the general principles accepted and observed by all humanity. Faith in these truths, which are real and essential laws, is precisely true submission to the laws of reason, just as obedience to laws is true faith in social beliefs. Remove submission to laws under the pretext that laws restrict human freedom, and immediately nothing remains but disorder and anarchy, which destroy all freedom. Remove faith in universal truths and principles, and you will have nothing left but doubt, which kills all knowledge.

Freedom does not consist in doing whatever one pleases—that is license. Freedom is the ability to do whatever is just, righteous, and in accordance with the law. The freedom to do what is unjust, unrighteous, and contrary to the law, or the freedom to do evil, is not true freedom; for in that case, even God would not be free, since God cannot do evil.

Thus, it is right to hinder and restrain everywhere, as much as possible, this freedom to do evil, which depends on human will, for with such freedom, no good can exist. Likewise, knowledge is not the ability to accept or reject whatever one pleases to accept or reject; in such an ability lies the source of all error. It overthrows and utterly destroys all principles that constitute universal reason, just as political or civil license is the overthrow and destruction of all laws that form society. There is no reason or knowledge without universal faith in general truths, just as there can be no society without general obedience to laws.

Alongside every right from which one benefits, there is always some duty to fulfill; one can never separate duty from right, nor right from duty. To deny a right is to remove a duty; to remove a duty is to overthrow a right. It is impossible to demand a duty from anyone without granting them some right. One cannot claim a right without being willing to fulfill some duties.

Holy Scripture warns us that those who praise us do not always love us, and that they often deceive and destroy us (Isaiah 3:12). Now, flatterers of thoughts are just as destructive as flatterers of passions. A person is equally deceived by being told that they are free to believe anything as by being told that they are free to do anything.

Flatterers of thoughts are the true troublemakers in the scientific order, who end up destroying all knowledge, just as demagogues are the true flatterers in the social order, who end up demolishing the entire structure of society.

Sciences that flatter us are not always those that can bring us salvation. Just as what is pleasant is not always useful, so what seems rational is not always true. There may be error in what seems reasoned, just as there is poison in sweetness. Conversely, just as there are things that are very unpleasant yet highly useful, so there are scientific systems that, though they seem unacceptable, are nevertheless very true.

Saint Paul said that one should not strive to know more than is necessary to know, and that moderation is as necessary in the scientific order as in the moral order: *Non plus sapere, quam oportet sapere, sed sapere ad sobrietatem* (Romans 12:3).

These are profound words. They mean that one must command one’s reason as one regulates the desire for food, and that intemperance in reasoning kills the spirit just as immoderation in eating kills the body.

Every good, of whatever kind, is always the reward of some suffering. Nature, as a pagan poet said, grants no benefits to humanity except as a reward for great sacrifices: *Nil sine magno labore vita dedit mortalibus* (Horace). This is humanity’s lot on earth. Whoever wishes to suffer nothing, to sacrifice nothing, is unworthy of any pleasure. One cannot acquire virtue without crucifying the heart; one cannot acquire knowledge without humbling the mind. Whoever cannot restrain their desires will never become virtuous; and whoever cannot subdue their thoughts will never become wise. Whoever seeks to enjoy everything will enjoy nothing; whoever demands to know everything on their own will know nothing. A person who desires all goods ends up possessing none; a person who seeks to acquire all knowledge ends up possessing no knowledge.

Thus, in condemning and rejecting as erroneous a philosophy that, starting from absolute doubt, believes it can discover all truth through its own means, the Catholic understanding did not deprive the human mind of its rightful claims. On the contrary, it ensured their use. It did not take away its noble faculties but facilitated their application. It merely redirected it to its natural state, to its proper destiny, which is to begin with faith in order to arrive at knowledge: *Nisi credideritis, non intelligetis.* In this way, the philosophy born of the Catholic understanding was not only rational in its aim but also natural in its principles, which will be the subject of the second part.

*To be continued.*

Religious and Moral Diary: a journal for the edification and benefit of both clergy and laity*, Vol. 24, No. 4 (April 1853).

Leave a comment